The drying Amazon rainforest: a drought that affects the world

The Amazon is suffering a drought of historic severity and it’s pushing its inhabitants to their limit

Few things speak so eloquently of the plight of the world’s biggest freshwater basin than the decaying carcasses of the Amazon’s pink river dolphins, says Um só Planeta (Rio de Janeiro).

Since mid-September, 130 of these beautiful, endangered creatures have washed up on riverbanks in and around Lake Tefé, which lies at the heart of Brazil’s Amazonas state. Much of the water has dried up – in September the Amazon fell 30cm a day over a period of two weeks – and such water as does remain is too hot for most dolphins, and for the thousands of fish, to survive in.

No fish to catch, no water to drink

The Amazon is suffering a drought of historic severity and it’s pushing its inhabitants to their limit, said Joan Royo Gual in El País (Madrid). The rivers of Brazil’s north are its highways, but now many are too shallow for canoes to navigate. So hundreds and thousands of people in jungle villages are stranded. There are no fish to catch. There’s little drinking water. And the giant hydroelectric plant on the Madeira River has had to shut its turbines.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The rest of Brazil is affected too, because Manaus, capital of Amazonas, is the industrial hub where many of Brazil’s TVs, dishwashers and air-con units are made. “All that merchandise leaves the city in trucks aboard rafts”– but maybe not for much longer. The weather system known as El Niño – an abnormal warming of surface waters in the Pacific – intermittently causes droughts in the Amazon region, said Wérica Lima in Amazônia Real (Rio de Janeiro), but its effects have been exacerbated this year by the simultaneous warming of waters in the North Atlantic brought on by climate change. Together, these systems have so inhibited the formation of clouds that rainfall in one city fell to a quarter of its normal September levels. And polluting smoke from the resulting forest fires has further inhibited rainfall.

Deforestation devastation

It’s not just down to the weather, said Lucas Ferrante on The Conversation. Deforestation is also a key part of the problem. With the land drier than ever, deforesters find it easy to burn vegetation and open up the land for soya or cattle pasture. And the building of the BR-319 highway, which is slicing through one of the most conserved blocks of forest and bringing deforesters with it, is making things worse.

Deforestation makes it ever harder for the rainforest to recover from droughts, said Alind Chauhan in The Indian Express (Delhi), and that ability to recover, as a study in Nature has shown, may have reached a tipping point. If it does tip, the lush green forest would turn into drier open savannah, release vast amounts of stored carbon, and accelerate global warming. That’s why the need to halt the deforestation is so vital. The Amazon may seem a distant world, but every corner of Earth is affected by its fate.

Continue reading for free

We hope you're enjoying The Week's refreshingly open-minded journalism.

Subscribed to The Week? Register your account with the same email as your subscription.

Sign up to our 10 Things You Need to Know Today newsletter

A free daily digest of the biggest news stories of the day - and the best features from our website

-

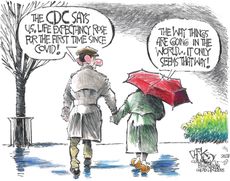

Today's political cartoons - December 3, 2023

Today's political cartoons - December 3, 2023Cartoons Sunday's cartoons - life expectancy goes up, Kissinger goes down, and more

By The Week US Published

-

10 things you need to know today: December 3, 2023

10 things you need to know today: December 3, 2023Daily Briefing Gaza residents flee as Israel continues bombardment, Trump tells supporters to 'guard the vote' in Democratic cities, and more

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

5 X-plosive cartoons about Elon Musk

5 X-plosive cartoons about Elon MuskCartoons Artists take on his proposed clean-up of X, his views on advertisers, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Places that will become climate refuges

Places that will become climate refugesThe Explainer The Midwest may become the new hotspot to move

By Devika Rao, The Week US Published

-

A23a: why world's biggest iceberg is on the move

A23a: why world's biggest iceberg is on the moveThe Explainer The mass of ice is four times the size of New York and 'essentially' an island

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK Published

-

Cop28: is UAE the right host for the climate summit?

Cop28: is UAE the right host for the climate summit?Today's Big Question Middle East nation is accused of 'pushing for a green world that can still have its oil'

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK Published

-

Want to understand climate change? Look to the clouds.

Want to understand climate change? Look to the clouds.The Explainer Scientists are still uncovering the role clouds play in climate change

By Devika Rao, The Week US Published

-

6 looming climate tipping points that imperil our planet

6 looming climate tipping points that imperil our planetThe Explainer A UN report details the thresholds we may be close to crossing

By Devika Rao, The Week US Published

-

'Danger to life' warning as Storm Ciarán hits UK shores

'Danger to life' warning as Storm Ciarán hits UK shoresSpeed Read Schools closed and train, plane and car travel disrupted as Met Office issues weather warnings

By The Week UK Published

-

Under Antarctic ice lies a hidden landscape

Under Antarctic ice lies a hidden landscapeSpeed Read Climate change may reveal it over time

By Devika Rao, The Week US Published

-

Could bacteria solve the world's plastic problem?

Could bacteria solve the world's plastic problem?The Explainer Scientists are genetically engineering bacteria to break down plastic

By Devika Rao Published