Psychiatrists turn to Ozempic to combat weight gain caused by psychotropic meds

The injectable weight loss drug could be a boon for those who take some antipsychotics or antidepressants.

Semaglutide injectables like Ozempic, Wegovy and Mounjaro have revolutionized how doctors treat diabetes and obesity. The drug has become a popular weight-loss tool, buoyed by its popularity among celebrities and a viral presence on social media. Now, per recent reports from The New York Times and Reuters, several psychiatrists have found another use for the sought-after drug: countering the weight gain that comes with taking antipsychotics and other mental health medicines.

Of the 13 mental health facilities and psychiatric departments the Times heard contacted, six said they actively prescribed or recommended drugs like Ozempic. In contrast, the others said they were not ready to try it, "citing concerns about safety and side effects and expressing a belief that prescribing weight-loss drugs was beyond their purview," the outlet reported. The group's responses illuminate an emerging debate in the psychiatric field about whether it is safe to prescribe the drug when there is "only a limited understanding of how people with serious mental illness fare on these medications."

Can semaglutide treat weight gain induced by some mental health medications?

Weight gain is a common side effect of many antipsychotics and mood stabilizers, which are typically prescribed for bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. However, some antidepressants can also lead to weight gain, though often to a lesser extent. The significant weight gain can "contribute to diabetes and heart disease, the leading cause of death among adults with schizophrenia," Reuters reported. Combined with external factors such as "inadequate access to healthy food," the outlet added, "over half of patients with bipolar depression and schizophrenia are overweight or obese."

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For some psychiatrists, the lack of research on how these drugs can affect weight is not enough of a deterrent to keep them from recommending them to their patients. Some argue that their patients cannot wait, especially if possible weight gain is standing in the way of them receiving critical treatment or contributing to life-threatening symptoms.

"Waiting until somebody has gained 50 pounds and has developed diabetes is just not serving the patient," Dr. Dost Ongur, chief of the psychotic disorders division of Mass General Brigham McLean Hospital, told Reuters. Semaglutitide injectibles have been "a real welcome addition" for patients who have "endured significant weight gain because of atypical antipsychotics and have doggedly tried their best to overcome that," Dr. Joseph Goldberg, a professor of psychiatry at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, told Reuters.

Psychiatrists have relied on diabetes medications like metformin and liraglutide to help patients fight weight gain, but "none have proven as powerful as the new drugs," the Times noted. Still, Ozempic is not yet a "go-to drug," Dr. Shebani Sethi, director of Stanford’s Metabolic Psychiatry program, told the Times. However, Sethi said she is still open to prescribing the drug as long as patients are aware of the risk.

What's keeping other psychiatrists from prescribing the drugs?

Some psychiatrists are hesitant to start prescribing semaglutide without enough data to prove it is safe and effective for their patients. "We are talking about a very vulnerable population," Dr. Mahavir Agarwal, a psychiatrist and scientist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, told the Times. There's "next to no data" on people with severe mental illnesses taking semaglutide, and until this changes, "you’re sort of flying blind," he added.

Other doctors are concerned by anecdotal reports from Europe of patients having suicidal thoughts while on Ozempic or Wegovy, Dr. Ilana Cohen, a psychiatrist at Sheppard Pratt in Maryland, told the outlet. The European Medicines Agency is currently reviewing reports of suicidal ideation on these drugs. Clinical trials of Wegovy purposely excluded people with recent suicidal thoughts, a history of suicide attempts, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and those who had been depressed within the past two years. "These medications were not studied well or designed for" patients with these tendencies, Cohen noted.

The medication's hefty price tag — about $1,3000 monthly — is also a concern, especially considering insurers are reluctant to cover the shots unless it's for diabetes. Some psychiatrists told Reuters that insurance providers had rejected their prescriptions, leading them to refer patients to an endocrinologist specializing in diabetes and obesity. Health plans have started adding restrictions to the use of Wegovy even though it is FDA-approved for treating obesity as a possible precursor for diabetes.

Continue reading for free

We hope you're enjoying The Week's refreshingly open-minded journalism.

Subscribed to The Week? Register your account with the same email as your subscription.

Sign up to our 10 Things You Need to Know Today newsletter

A free daily digest of the biggest news stories of the day - and the best features from our website

Theara Coleman has worked as a staff writer at The Week since September 2022. She frequently writes about technology, education, literature and general news. She was previously a contributing writer and assistant editor at Honeysuckle Magazine, where she covered racial politics and cannabis industry news.

-

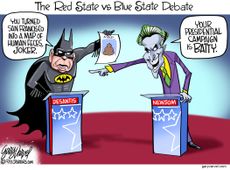

Today's political cartoons - December 2, 2023

Today's political cartoons - December 2, 2023Cartoons Saturday's cartoons - governors go Gotham, A.I. goes to the office party, and more

By The Week US Published

-

10 things you need to know today: December 2, 2023

10 things you need to know today: December 2, 2023Daily Briefing Death toll climbs in Gaza as airstrikes intensify, George Santos expelled from the House of Representatives, and more

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

5 hilarious cartoons about the George Santos expulsion vote

5 hilarious cartoons about the George Santos expulsion voteCartoons Artists take on Santa versus Santos, his X account, and more

By The Week US Published

-

5 tips for dealing with grief during the holiday season

5 tips for dealing with grief during the holiday seasonThe Explainer Finding your holiday cheer might be more complicated when you're grieving. But it's not impossible.

By Theara Coleman, The Week US Published

-

Anger may be a powerful motivator for tough goals, new study suggests

Anger may be a powerful motivator for tough goals, new study suggestsSpeed Read Keeping your cool might actually be less efficient than letting your anger drive you

By Theara Coleman, The Week US Published

-

Skeletal remains debunk myth around 1918 flu pandemic

Skeletal remains debunk myth around 1918 flu pandemicUnder the Radar New research casts doubt on widely held assumption that 1918 virus predominantly affected the young and healthy

By The Week Staff Published

-

Heat harms the brain more than we think

Heat harms the brain more than we thinkWarmer temperatures could be affecting us mentally

By Devika Rao Published

-

Jonah Hill and the rise of therapy speak

Jonah Hill and the rise of therapy speakTalking Point Film star’s texts to former girlfriend highlight new desire to apply language of psychotherapy to everyday life

By Sorcha Bradley Published

-

The ‘dramatic’ rise of ADHD

The ‘dramatic’ rise of ADHDfeature Diagnoses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder have risen sharply in the UK

By The Week Staff Published

-

The debate over police and mental health crisis care

The debate over police and mental health crisis careTalking Point Commissioner says current approach to crises is “untenable”

By Rebekah Evans Published

-

Good health news: seven surprising medical discoveries made in 2023

Good health news: seven surprising medical discoveries made in 2023In Depth A fingerprint test for cancer, a menopause patch and the shocking impacts of body odour are just a few of the developments made this year

By The Week Staff Published