Magic mushrooms and the mind

A growing number of states and cities are legalizing the use of psychedelic fungi in therapy. Some experts think that’s a big risk.

A growing number of states and cities are legalizing the use of psychedelic fungi in therapy. Some experts think that’s a big risk. Here's everything you need to know:

Are 'magic mushrooms' legal?

Not under federal law, which has classified the fungi as a highly dangerous Schedule 1 drug since 1970. But a campaign to decriminalize psilocybin, the mind-altering compound in magic mushrooms, is gaining pace at the state and local level. This summer, Oregon became the first state to allow the use of psilocybin in mental health care. Colorado intends to follow suit in 2025 and San Francisco; Detroit; Washington, D.C.; and other cities have voted in recent years to decriminalize psilocybin. At licensed therapy facilities in Oregon, patients take mushrooms from a state-approved grower under the guidance of a certified facilitator, or "trip sitter." The effect is much more than "rainbows and unicorns," Josh Goldstein, a psilocybin facilitator in Bend, told The New York Times. At one recent session overseen by Goldstein, a Marine veteran struggling with PTSD said the psilocybin triggered visions of colorful ribbons wrapping around painful thoughts. "It was like a massive weight had been released," said the veteran. It sounds rather trippy, but a growing body of research indicates psilocybin could help relieve depression, addiction, anxiety and many other mental health conditions. "There is a lot of hype," said Dr. Joshua Gordon, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, "and a lot of hope."

How does psilocybin therapy work?

Research suggests that psilocybin can rewire the brain by generating new connections between neurons. The feeling of altered consciousness experienced during a mushroom trip — including kaleidoscopic visions and hallucinations — is a result of unusual linkages forming among parts of the brain that handle auditory and visual information, and executive and sense-of-self functions. Such disruption can be therapeutic, said David Nutt, a psychopharmacologist at Imperial College London. "Depressed people are continually self-critical and they keep ruminating, going over and over the same negative, anxious, or fearful thoughts," he explains. Psilocybin breaks the brain out of that familiar pattern so "critical thoughts are easier to control and thinking is more flexible."

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How long do the effects last?

Psilocybin’s immediate psychedelic effects typically peak about 60 to 90 minutes after the drug has been consumed, but can go on for up to eight hours. The new brain connections forged during those trips last much longer — at least a month in mice treated with psilocybin. Such long-lasting effects might eventually allow people with depression to curb their use of traditional antidepressants, perhaps taking the medications only once a week or month, said David Olson, a psychedelics expert at University of California, Davis. Growing awareness of psilocybin’s possible mental health applications has led the FDA to label the chemical a "breakthrough therapy" for depression and anxiety, and the Department of Veterans Affairs is now participating in at least five trials of psilocybin and other psychedelics for treating PTSD and other conditions. Still, some researchers see dangers in the push to make psilocybin more widely available.

Why are they worried about?

Psilocybin can trigger psychotic episodes and lead people to make dreadful decisions. An off-duty pilot riding in an extra cockpit seat on a Horizon Air flight last month tried to cut off the San Francisco-bound plane’s engine mid-flight. Joseph Emerson — who was charged with 83 counts of attempted murder, one for each person onboard — told police afterward that he’d been severely depressed and had taken magic mushrooms for the first time 48 hours earlier. He grabbed the emergency handles, he said, because he was trying to wake up from a dream. Some experts were skeptical, saying the drug should have been long gone from his system. Yet The American Journal of Psychiatry last year published a case study describing how a 32-year-old accountant suffered weeks of delusions, mania and psychosis after taking mushrooms with friends. She required months of intense psychiatric treatment to emerge from crippling depression. "I [am] shocked at the legislative momentum" for expanding psychedelics access, said Washington University psychiatrist Joshua Siegel.

Is broader legalization imminent?

The push suffered a setback in early October when California Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed a bill to decriminalize mushrooms and two other plant-based hallucinogens. "Do you really want people that are tripping on mushrooms driving cars?" asked Brian Marvel, president of an 80,000-member law enforcement organization that opposed the bill. The Horizon Air incident, which occurred two weeks after Newsom’s veto, has only added fuel to such arguments. Psilocybin advocates in the U.S. are divided over the best path forward. Medicalized regulation is safer, but more expensive: In Oregon, a six-hour guided trip can cost more than $3,000. Decriminalization, however, might lead many people to think they can solve their problems by popping a shroom, something health experts say should occur in supervised settings in conjunction with talk therapy. The FDA is widely expected to approve psilocybin for depression by the end of the decade. But that will require clinical studies much larger than any conducted to date; the largest trial so far included 233 patients in North America and Europe. "What we don’t know," said Fred Barrett, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, "way outstrips what we do know."

The ancient roots of 'God’s flesh'

Humanity’s relationship with psychedelic fungi goes way back. Some researchers believe the first evidence of psilocybin use can be seen in 10,000-year-old cave paintings in Western Australia, which depict people with mushroom-like heads. There’s much stronger evidence of Indigenous Americans incorporating psilocybin in rituals. The Aztecs of Mexico called the mushroom teonanácatl, or "flesh of the gods." In the 16th century, the Dominican friar Diego Durán recorded the fungi being consumed at Aztec religious feasts. "Those who eat them see visions and feel a fluttering of the heart," he wrote. "Those few who eat them in excess are driven to lust." Psilocybin entered the U.S. consciousness in the 1950s, after R. Gordon Wasson, a vice president of J.P. Morgan and an amateur ethnobotanist, traveled to Oaxaca to sample "divine mushrooms" prepared by a Mexican medicine woman. Wasson detailed the experience in a 1957 Life article titled "Seeking the Magic Mushroom." His travelogue inspired other Americans to visit Oaxaca and scarf shrooms; among them was Harvard psychologist and soon-to-be psychedelic evangelist Timothy Leary. That first psilocybin trip, said Leary, was "the deepest religious experience of my life."

Continue reading for free

We hope you're enjoying The Week's refreshingly open-minded journalism.

Subscribed to The Week? Register your account with the same email as your subscription.

Sign up to our 10 Things You Need to Know Today newsletter

A free daily digest of the biggest news stories of the day - and the best features from our website

-

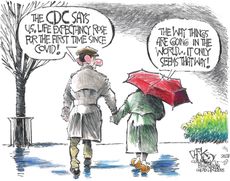

Today's political cartoons - December 3, 2023

Today's political cartoons - December 3, 2023Cartoons Sunday's cartoons - life expectancy goes up, Kissinger goes down, and more

By The Week US Published

-

10 things you need to know today: December 3, 2023

10 things you need to know today: December 3, 2023Daily Briefing Gaza residents flee as Israel continues bombardment, Trump tells supporters to 'guard the vote' in Democratic cities, and more

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

5 X-plosive cartoons about Elon Musk

5 X-plosive cartoons about Elon MuskCartoons Artists take on his proposed clean-up of X, his views on advertisers, and more

By The Week US Published

-

4 tips for protecting your skin during winter

4 tips for protecting your skin during winterThe explainer The temperature drop could make anyone susceptible to dryer skin. Time to switch up your skin care routine.

By Theara Coleman, The Week US Published

-

How polysubstance abuse is worsening the American opioid crisis

How polysubstance abuse is worsening the American opioid crisisThe Explainer Studies are showing that more Americans are struggling with dependency on multiple substances.

By Theara Coleman, The Week US Published

-

Kush: the drug destroying young lives in West Africa

Kush: the drug destroying young lives in West AfricaThe Explainer There has been a sharp rise in young addicts in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia

By Flora Neville, The Week UK Published

-

What's the microbiome and why is it so important?

What's the microbiome and why is it so important?The Explainer Our bodies serve as vibrant ecosystems for trillions of microbes

By Devika Rao, The Week US Published

-

5 tips for dealing with grief during the holiday season

5 tips for dealing with grief during the holiday seasonThe Explainer Finding your holiday cheer might be more complicated when you're grieving. But it's not impossible.

By Theara Coleman, The Week US Published

-

Ageing boomers: America’s looming crisis

Ageing boomers: America’s looming crisisUnder the radar A person turning 65 today in US has an almost 70% chance of needing long-term care

By The Week Staff Published

-

Marijuana use associated with heart attack and stroke

Marijuana use associated with heart attack and strokeSpeed Read Two new studies point to an increased risk of cardiovascular problems

By Devika Rao, The Week US Published

-

The fight against malaria

The fight against malariaThe Explainer After declining for decades, deaths from the disease are suddenly on the rise. What’s changed?

By The Week US Published