Extreme heat: how deadly will it be by 2030?

Heatwaves fuelled by climate crisis are one of ‘gravest threats’ to humanity

Extreme heat represents one of the “gravest threats to humanity”, according to a new study, as countries all over the world battle record-breaking temperatures fuelled by climate change and the weather pattern known as El Niño.

Analysis by The Washington Post suggests that by 2030, about four billion people will be exposed to “at least a month of health-threatening extreme heat when outdoors” every year, up from two billion at the turn of the century. This “epidemic of extreme heat” will be concentrated in some of the world’s poorest regions, places “least prepared to cope”.

A “brutal” heatwave is gripping a “huge swathe of the central US”, said NBC News, with more than 100 million Americans – nearly a third of the population – under heat alerts. “Extreme heat causes more deaths across the US each year than any other weather event.”

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This week officials in England implemented amber warnings in eight out of nine regions, due to forecast high temperatures. Millions of Europeans have been sweltering in record temperatures brought on by the Cerberus heatwave, with several countries “set ablaze by unprecedented forest fires”, said The Evening Standard.

In South America, an “unprecedented winter heatwave” is drying up the world’s highest navigable lake, said CNN. Water levels at Lake Titicaca, on the Peru-Bolivia border, are “dropping precipitously”, threatening the lives and livelihoods of the three million people who live alongside it.

What did the papers say?

The Washington Post combined scientific studies with “massive” climate data sets and projections from Nasa, to reach “one of the most detailed estimates of current and future heat stress at a local level ever produced”. It concluded that by 2030, 500 million people around the world would be exposed to extreme, illness-causing heat for at least a month a year – “even if they can get out of the sun”.

More than half of those (270 million) live in India, and nearly 190 million in Pakistan. In both countries, outdoor labourers make up about half the workforce, who are particularly at risk of kidney disease, heart attacks and strokes.

Extreme heat will exacerbate the spread of diseases like malaria, as they are “tied to hotter temperatures, and swifter passages of pathogens and toxins”. The world is “ill prepared for the insidious, intensifying risks to almost every facet of human health”, it concluded.

What is “particularly dangerous” is the combination of high heat and humidity, said NBC News. When that figure exceeds the temperature of the human body, about 37C, it starts to “brush up against the limits of human survivability”.

Extreme temperatures combined with air pollution can also double the risk of dying from a heart attack, according to a study by Chinese researchers published in July.

And the effects of heat do not stop there. “When the temperature spikes, so too do suicide rates, crime, and violence,” said Time. A study in The Lancet Planetary Health showed that an increase in temperature of 1% above the norm contributed to a higher probability of depression and anxiety.

But people tend to feel uncertain of what to do about heat, said Scientific American, “and don’t perceive as much personal risk” as with other extreme weather events. This “mismatch” between the danger and action “extends beyond individual perception to the policy level”, with heat risks “often not prioritised in climate mitigation and adaptation plans – if they are factored in at all”.

What next?

“Heatwaves are becoming more likely and more extreme because of climate change,” said BBC News. The global average temperature in July was the highest of any month on record, according to Europe’s Copernicus Climate Change Service.

Even if countries deliver on their emission reduction pledges under the Paris agreement, the UN Environment programme estimates at least a 2.5C rise in global temperatures by the end of the century.

The UK must “adapt urgently”, wrote Emma Hill and Ben Vivian (sustainability professors at Coventry University) for The Conversation, by making changes to social, economic and ecological systems to reduce the impact of heatwaves.

A recent paper in Nature Sustainability estimated that there are about 570,000 homes and other buildings, such as hospitals, in the UK which are unable to deal with the projected 2C global warming. “Such buildings will need retrofitting with cooling systems, better ventilation and natural or artificial shading,” wrote Hill and Vivian.

Just how bad it gets will depend on “how much humanity curbs climate change”, said The New York Times. “But some of the far-reaching effects of extreme heat are already inevitable, and they will levy a huge tax on entire societies – their economies, health and way of life.”

Continue reading for free

We hope you're enjoying The Week's refreshingly open-minded journalism.

Subscribed to The Week? Register your account with the same email as your subscription.

Sign up to our 10 Things You Need to Know Today newsletter

A free daily digest of the biggest news stories of the day - and the best features from our website

Harriet Marsden is a writer for The Week, mostly covering UK and global news and politics. Before joining the site, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, specialising in social affairs, gender equality and culture. She worked for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent, and regularly contributed articles to The Sunday Times, The Telegraph, The New Statesman, Tortoise Media and Metro, as well as appearing on BBC Radio London, Times Radio and “Woman’s Hour”. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, London, and was awarded the "journalist-at-large" fellowship by the Local Trust charity in 2021.

-

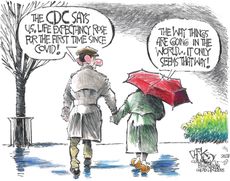

Today's political cartoons - December 3, 2023

Today's political cartoons - December 3, 2023Cartoons Sunday's cartoons - life expectancy goes up, Kissinger goes down, and more

By The Week US Published

-

10 things you need to know today: December 3, 2023

10 things you need to know today: December 3, 2023Daily Briefing Gaza residents flee as Israel continues bombardment, Trump tells supporters to 'guard the vote' in Democratic cities, and more

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

5 X-plosive cartoons about Elon Musk

5 X-plosive cartoons about Elon MuskCartoons Artists take on his proposed clean-up of X, his views on advertisers, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Cop28: is UAE the right host for the climate summit?

Cop28: is UAE the right host for the climate summit?Today's Big Question Middle East nation is accused of 'pushing for a green world that can still have its oil'

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK Published

-

Sunak house protest: is all fair in the fight against climate change?

Sunak house protest: is all fair in the fight against climate change?Today's Big Question Action by ‘self-obsessed zealots’ is condemned by some, but do less confrontational tactics work?

By Chas Newkey-Burden Published

-

Does the UK need more North Sea oil and gas?

Does the UK need more North Sea oil and gas?Today's Big Question Experts say new drilling can’t ‘magically’ stop output collapse

By Chas Newkey-Burden Published

-

Will Sunak and Starmer drop green policies to win voters?

Will Sunak and Starmer drop green policies to win voters?Today's Big Question Conservatives and Labour draw same conclusion from shock Uxbridge result but are warned move would be ‘political suicide’

By The Week Staff Published

-

Why is Thames Water struggling to stay afloat?

Why is Thames Water struggling to stay afloat?Today's Big Question The UK’s largest water company could be nationalised after amassing huge debts

By Richard Windsor Published

-

Has the world finally reached ‘peak oil’?

Has the world finally reached ‘peak oil’?Today's Big Question Experts think the shift to clean energy is quickening but one says we should take the forecast with ‘a boulder of salt’

By Chas Newkey-Burden Published

-

What’s caused the big stink over Britain’s sewage?

What’s caused the big stink over Britain’s sewage?Today's Big Question Clean water a ‘politically charged issue’ as government sets outs plans to clean up rivers and coastal areas

By The Week Staff Published

-

UK’s ‘green day’: is net zero achievable?

UK’s ‘green day’: is net zero achievable?Today's Big Question ‘Powering up Britain’ plan slammed as ‘re-announcements, reheated policy and no new investment’

By Hollie Clemence Published