Europe’s migration crisis: how radical are the responses?

Germany and Italy announce new tighter restrictions as tide turns on open borders

"Olaf Scholz is getting desperate," said Matthew Karnitschnig on Politico (Brussels). The financial pressures and public upset caused by the rising tide of asylum seekers is making his coalition government increasingly unpopular.

Germany is already home to three million refugees – Ukrainians included; and this year has already seen a 70% rise in asylum applications, and there are still two months to go. So Scholz found himself hammering out a deal last week with Germany's 16 state governors aimed at curbing the numbers.

"I don't want to use big words," the famously subdued chancellor said afterwards, "but I think this is a historic moment." He may well be right, but only because this hugely underwhelming agreement could well mark "the beginning of his political end". Its array of "cosmetic measures" includes a plan to ensure that new arrivals wait three years before receiving welfare payments; an increase in federal aid for state governments; and ambitious (but unattainable) targets to speed up deportations. But the radical steps needed to have any chance of reducing numbers? These are entirely missing.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

'Problem isn't as dire as people make out'

The agreement may be imperfect, said Daniel Friedrich Sturm in Der Tagesspiegel (Berlin), but at least it shows Scholz's centre-left coalition has finally grasped the urgency of the issue, and is willing to work with its opponents in states run by centre-right Christian Democrats to address it. In any case, the problem isn't as dire as people make out, said Gesine Schwan in Süddeutsche Zeitung (Munich). Even if asylum applications hit 350,000 this year, that's still less than half the 745,545 applications submitted in 2016. The impression of being overwhelmed is due to the one-off influx of a million Ukrainians last year, all admitted without the need to apply for asylum.

Maybe so, said Cécile Boutelet in Le Monde (Paris), but the recent rise in numbers is still a hugely divisive issue: 73% of Germans say they're dismayed at the government's handling of it; one in five say they may vote for the hard-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party, which is enjoying a surge of support. That's why last week's deal included a provision to at least consider a radical "course correction" in policy, said Oliver Maksan in Neue Zürcher Zeitung (Zurich). Until now, the idea of relocating asylum procedures abroad has been off limits for Germany. In EU Council negotiations in June, for example, Scholz's government had insisted a "connection criterion" must apply to any asylum seekers being sent to a third country – it had to be a country they already had some connection with. In now calling for an inquiry into the merits of "extraterritorial asylum centres", the government is "jumping over its own shadow".

'All credit to Meloni for grasping the nettle'

Yet that's the way the wind is blowing, said Benjamin Fox on Euractiv (Brussels). Austria has linked up with Britain in a plan to fly asylum seekers to Kigali for their claims to get processed (though unlike Britain, they won't then have to stay in Rwanda if their application is successful). Denmark is working on setting up an asylum processing centre in a central African nation; and most striking of all, Italy struck a deal last week to build two offshore holding centres for migrants in Albania. The agreement between Italy's PM Giorgia Meloni and Albania's Edi Rama came "like a bolt from the blue", said Alessandro Sallusti in Il Giornale (Milan). It's a win-win deal. Albania needs Rome's support in its push to join the EU, Italy urgently needs a radical solution to managing the migratory flows across the Mediterranean. All credit to Meloni for grasping the nettle.

On the contrary, the deal is a mirage, said Andrea Bonanni in La Repubblica (Rome). The 36,000 people a year rescued from the Mediterranean who'll be sent to the centres in Albania financed and managed by Italy can't stay there indefinitely: if denied asylum, they'll simply make their way back to Italy via Croatia. This deal, and others like it, won't solve the difficulties encountered in trying to repatriate such people. Don't be fooled: "the Albanian patch won't be able to cover the Italian hole".

Continue reading for free

We hope you're enjoying The Week's refreshingly open-minded journalism.

Subscribed to The Week? Register your account with the same email as your subscription.

Sign up to our 10 Things You Need to Know Today newsletter

A free daily digest of the biggest news stories of the day - and the best features from our website

-

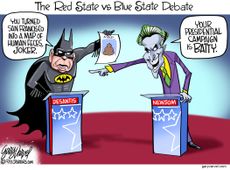

Today's political cartoons - December 2, 2023

Today's political cartoons - December 2, 2023Cartoons Saturday's cartoons - governors go Gotham, A.I. goes to the office party, and more

By The Week US Published

-

10 things you need to know today: December 2, 2023

10 things you need to know today: December 2, 2023Daily Briefing Death toll climbs in Gaza as airstrikes intensify, George Santos expelled from the House of Representatives, and more

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

5 hilarious cartoons about the George Santos expulsion vote

5 hilarious cartoons about the George Santos expulsion voteCartoons Artists take on Santa versus Santos, his X account, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Worklessness: a national 'scandal'

Worklessness: a national 'scandal'Talking Point One in five working-age adults in Birmingham, Glasgow and Liverpool are neither in work nor seeking work

By The Week UK Published

-

Alleged Sikh assassination plot rocks US-India relations

Alleged Sikh assassination plot rocks US-India relationsTalking Point By accusing an Indian government official of orchestrating an assassination attempt on a US citizen in New York, the Justice Department risks a diplomatic crisis between two superpower

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

Dublin riots: a blow to Ireland’s reputation

Dublin riots: a blow to Ireland’s reputationTalking Point Unrest shines a spotlight on Ireland's experience of mass migration

By The Week UK Published

-

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?Talking Point Top US diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize winner remembered as both foreign policy genius and war criminal

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Last updated

-

The Supreme Court could reign in the SEC — and federal agencies as a whole

The Supreme Court could reign in the SEC — and federal agencies as a wholeTalking Point The court is hearing arguments on the agency's ability to enforce financial penalties

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

Is the Ukraine government and its military on brink of a split?

Is the Ukraine government and its military on brink of a split?Today's Big Question Public spats between President Zelenskyy and his military chief have contributed to declining morale within Ukraine

By Richard Windsor, The Week UK Published

-

America doesn't have a wealth tax. The Supreme Court might kill it anyway.

America doesn't have a wealth tax. The Supreme Court might kill it anyway.Talking Point Justices are being asked to do something unusual: issue opinions about hypothetical legislation

By Joel Mathis, The Week US Published

-

How a long-term truce in Gaza could have ripple effects across the Middle East

How a long-term truce in Gaza could have ripple effects across the Middle EastTalking Point Israel and Hamas have recently agreed to extend their peace for two more days

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published