Covid-19: where are we now?

Hospital admissions for patients with the virus have been falling since October

Hospital admissions for people in England testing positive for Covid-19 have dropped for the fifth week in a row, following a rise in cases over the summer.

The number of Covid hospital admissions in the week to 12 November stood at 2.8 per 100,000, down from 3.4 the previous week, according to the latest data from the UK Health Security Agency (UKSA). Hospitalisations were at their highest among those in the 85 years and over age group.

Covid-19 cases rose over the summer, driven by the emergence of new Omicron variants, but the numbers of people testing positive and being admitted to hospital has now been falling since mid-October.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As a further point of comparison, at this point last year the hospital admission rate was 5.1 per 100,000, down from 5.4 the previous week. But the number of hospital admissions would later peak at 11.4 in the run-up to last Christmas.

Is Covid a 'winter bug'?

Covid cases last year peaked in December. But experts have cautioned against assuming that the coronavirus will follow the pattern of other respiratory infections and become a winter illness.

Although transmission increases as people mix indoors during the colder months, the same is also true in very hot weather, as people head inside to escape the heat.

"It seems like patterns of waning [immunity] and the evolution of [the] virus itself are still the main drivers for the sort of variation that we're seeing," said Professor Steven Riley, director general of data, analytics and surveillance at UKHSA, speaking to The Guardian in October. "[Covid] doesn't seem to have dropped into any kind of resonance with seasonal factors."

However, with pressure increasing on the health service over the winter period, NHS England is urging eligible people to get flu and Covid jabs to avoid a potential "twindemic".

How concerned should we be about new variants?

Two years on from the first cases of Omicron, sub-variants continue to emerge.

While those such as Eris remain the dominant forms around the world, BA.2.86, otherwise known as Pirola, has recently become the focus of global medical attention, having "sparked a rise in hospitalisations and prompted governments to bring forward booster vaccines", reported Euronews.

According to Yale Medicine, BA.2.86 has more than 30 mutations to its spike protein. The impact of these mutations will "become clearer as more data emerges", said the World Economic Forum (WEF), "but scientists predict it may be harder for our immune system to recognise Pirola, and to mount a strong response".

Initial evidence shows Pirola is "not causing more severe illness and that existing tests and medications used for Covid-19 are effective", said WEF, but the new variant may be "more capable of causing infection and evading vaccines".

In September, Professor Stephen Griffin, co-chair of Independent Sage, warned that the latest Covid strains could be "forebearers" of potentially worse variants to come.

"The perception we're done with it and the narrative of having to live with it is another way of saying we're willing to deal with the damage it does," the leading virologist told the Daily Mirror. "It's the opposite of the emperor's new clothes."

Could a new variant lead to restrictions being reimposed?

The chance of a particularly concerning new variant emerging is "too high to turn your back on", Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in San Diego, told the Financial Times in August.

Experts surveyed by Topol reportedly put the chances of an "Omicron-like event" – which would put considerable pressure on the NHS, as well as causing widespread workplace disruption – occurring before 2025 at between 10% and 20%.

And if a variant emerges that is more transmissible than Omicron then "all bets are off", said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the University of Saskatchewan.

The result would almost certainly be an increase in cases "wherever there was a nice susceptible population, and not necessarily just in winter when conditions are very good for transmission", she continued. "We haven't seen the end of this virus. It's going to acquire mutations and that has unpredictable results."

Should we be wearing masks again?

The UK and many other countries have "moved to a position of 'living with the virus' without investing in testing, ventilation and infrastructure changes, and masking", wrote immunologist Sheena Cruickshank, a professor in biomedical sciences at Manchester University, in The Guardian.

But "add to this that vaccine coverage and access to boosters is quite limited, and there’s a recipe for many Covid infections – and a greater likelihood of the virus changing".

The question of whether to mask again is a "complicated" one, said Simon Clarke, associate professor in cellular microbiology at Reading University.Masking was introduced in the UK in 2020, as part of a wide package of measures.

Yet masks "did not prevent subsequent waves of infections and lockdowns", Clarke said in an article on The Conversation this August. "It seems unlikely that masking on its own, without other measures, would have much effect, if any."

Continue reading for free

We hope you're enjoying The Week's refreshingly open-minded journalism.

Subscribed to The Week? Register your account with the same email as your subscription.

Sign up to our 10 Things You Need to Know Today newsletter

A free daily digest of the biggest news stories of the day - and the best features from our website

Sorcha Bradley is a writer at The Week and a regular on “The Week Unwrapped” podcast. She worked at The Week magazine for a year and a half before taking up her current role with the digital team, where she mostly covers UK current affairs and politics. Before joining The Week, Sorcha worked at slow-news start-up Tortoise Media. She has also written for Sky News, The Sunday Times, the London Evening Standard and Grazia magazine, among other publications. She has a master’s in newspaper journalism from City, University of London, where she specialised in political journalism.

-

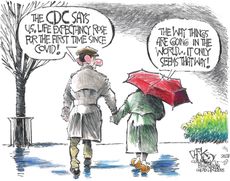

Today's political cartoons - December 3, 2023

Today's political cartoons - December 3, 2023Cartoons Sunday's cartoons - life expectancy goes up, Kissinger goes down, and more

By The Week US Published

-

10 things you need to know today: December 3, 2023

10 things you need to know today: December 3, 2023Daily Briefing Gaza residents flee as Israel continues bombardment, Trump tells supporters to 'guard the vote' in Democratic cities, and more

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

5 X-plosive cartoons about Elon Musk

5 X-plosive cartoons about Elon MuskCartoons Artists take on his proposed clean-up of X, his views on advertisers, and more

By The Week US Published

-

4 tips for protecting your skin during winter

4 tips for protecting your skin during winterThe explainer The temperature drop could make anyone susceptible to dryer skin. Time to switch up your skin care routine.

By Theara Coleman, The Week US Published

-

China's pneumonia cases: should we be worried?

China's pneumonia cases: should we be worried?The Explainer Experts warn against pushing 'pandemic panic button' following outbreak of respiratory illness

By Keumars Afifi-Sabet, The Week UK Published

-

How polysubstance abuse is worsening the American opioid crisis

How polysubstance abuse is worsening the American opioid crisisThe Explainer Studies are showing that more Americans are struggling with dependency on multiple substances.

By Theara Coleman, The Week US Published

-

Vallance diaries: Boris Johnson 'bamboozled' by Covid science

Vallance diaries: Boris Johnson 'bamboozled' by Covid scienceSpeed Read Then PM struggled to get his head around key terms and stats, chief scientific advisor claims

By The Week UK Published

-

Kush: the drug destroying young lives in West Africa

Kush: the drug destroying young lives in West AfricaThe Explainer There has been a sharp rise in young addicts in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia

By Flora Neville, The Week UK Published

-

Why infant mortality is rising

Why infant mortality is risingThe Explainer The infant mortality rate recently rose for the first time in two decades

By Devika Rao, The Week US Published

-

5 tips for dealing with grief during the holiday season

5 tips for dealing with grief during the holiday seasonThe Explainer Finding your holiday cheer might be more complicated when you're grieving. But it's not impossible.

By Theara Coleman, The Week US Published

-

The CDC has a new plan to address the health care worker burnout crisis

The CDC has a new plan to address the health care worker burnout crisisThe Explainer The program puts the pressure on health care leaders to lift some of the burdens of their employees

By Theara Coleman, The Week US Published