Blavatnik Galleries review: how art is war's 'most truthful witness'

New space displays some of the Imperial War Museum's finest art, film and photography

Since it was founded in 1917, London's Imperial War Museum has quietly built up a vast collection of art created in response to conflict, said Simon Heffer in The Daily Telegraph. Its holdings include not only "some of the finest paintings of warfare in the nation's possession", but also hundreds of drawings, prints and sculptures, as well as some "12 million photographs, and 23,000 hours of film footage". Where previously this "fine" trove of art and images was scattered throughout the museum, it now has a dedicated home courtesy of a purpose-built extension that at long last gives the public a chance to fully appreciate it. The new Blavatnik Art, Film and Photography Galleries contain all manner of materials, from wartime masterpieces by the likes of Eric Ravilious and Paul Nash to art created in response to recent conflicts in the Middle East, as well as ephemera including "propaganda posters", "documentary footage of battle" and newsreel films. If there is one complaint about this "handsome" display, it is that it "could never hope to be big enough".

In the context of today's geopolitics, the new space feels "not just topical, but essential", said Stuart Jeffries in The Guardian. The centrepiece of the gallery is John Singer Sargent's epic "Gassed", six metres wide, depicting "a procession of wounded men stumbling, blindfolded, towards a dressing station". Other works range from the angry – Peter Kennard and Cat Phillipps's 2007 photomontage of Tony Blair "holding his phone for a selfie against a background of burning oilfields" – to the reflective. Steve McQueen, appointed an official war artist in 2003, commemorated each of the 179 UK military personnel killed in Iraq with a postage stamp, juxtaposing images of the dead soldiers with "the silhouetted head of the Queen". The stamps were deemed too controversial for Royal Mail to issue – almost, McQueen suggested, as if people were "ashamed" of the dead.

"There is enough engrossing material on display here to keep you sobbing for a week," said Waldemar Januszczak in The Sunday Times. Doris Zinkeisen, the first official artist to enter Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, for instance, depicted its inmates as "grotesquely skeletal and white, thrown out of the death huts like discarded rubbish". More subtly, Walter Sickert's "Tipperary" (1914) sees a woman at a piano in one of his trademark "gloomy" interiors: "the mournful notes counting the miles to Tipperary are as audible as a party next door". Meanwhile, documentary material including letters, timelines and photographs "keep us grounded in the facts". If the Imperial War Museum once felt like a "spooky" institution without a clear role, the new galleries grant it "gravitas and sincerity". The Blavatnik Galleries have "achieved extreme pertinence", and confirm art as "war's most truthful witness".

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Imperial War Museum, London SE1 (020-7416 5000, iwm.org.uk). Now open (free entry)

Sign up to The Week's Arts & Life newsletter for reviews and recommendations

Continue reading for free

We hope you're enjoying The Week's refreshingly open-minded journalism.

Subscribed to The Week? Register your account with the same email as your subscription.

Sign up to our 10 Things You Need to Know Today newsletter

A free daily digest of the biggest news stories of the day - and the best features from our website

-

10 things you need to know today: December 3, 2023

10 things you need to know today: December 3, 2023Daily Briefing Gaza residents flee as Israel continues bombardment, Trump tells supporters to 'guard the vote' in Democratic cities, and more

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

5 X-plosive cartoons about Elon Musk

5 X-plosive cartoons about Elon MuskCartoons Artists take on his proposed clean-up of X, his views on advertisers, and more

By The Week US Published

-

2023: the year of superhero fatigue

2023: the year of superhero fatigueThe Explainer The year may represent the end of an era for Hollywood

By Brendan Morrow, The Week US Published

-

Recipe: roast garlic mushrooms with parsley and eggs by Gelf Alderson

Recipe: roast garlic mushrooms with parsley and eggs by Gelf AldersonThe Week Recommends A simple and classic breakfast combination

By The Week UK Published

-

Shein: the biggest Wall Street float of 2024?

Shein: the biggest Wall Street float of 2024?Speed Read Clothing industry disruptor is about to test its acceptability on the US stock market

By The Week UK Published

-

A Neolithic marvel in southeast Turkey

A Neolithic marvel in southeast TurkeyThe Week Recommends A trip to Göbekli Tepe offers visitors the chance to explore nearby Sanlıurfa

By The Week UK Published

-

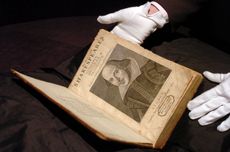

Shakespeare's First Folio: 400 years in print

Shakespeare's First Folio: 400 years in printThe Explainer First published in 1623, seven years after his death, the weighty tome includes Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, Julius Caesar

By The Week UK Published

-

Properties of the week: stunning houses for winter sun

Properties of the week: stunning houses for winter sunThe Week Recommends Featuring a beachfront cottage in Grand Cayman and a villa in Costa Rica with sea and jungle views

By The Week UK Last updated

-

Christmas 2023: best stocking fillers and Secret Santa gifts

Christmas 2023: best stocking fillers and Secret Santa giftsThe Week Recommends The wish list includes boozy crackers, slippers, bath treats, socks and chocs

By The Week UK Published

-

6 welcoming homes great for family gatherings

6 welcoming homes great for family gatheringsFeature Featuring a home with 13 fireplaces in Maine and a home with heated brick floors in New Mexico

By The Week US Published

-

Christmas 2023: best food and drink hampers

Christmas 2023: best food and drink hampersThe Week Recommends Everything you need for a festive feast – from the turkey and trimmings to the dessert, cheese and wine

By The Week UK Published