A nation moving apart

Americans are increasingly sorting themselves into communities with shared politics. Is this bad for democracy?

Americans are increasingly sorting themselves into communities with shared politics. Is this bad for democracy? Here's everything you need to know:

How politically segregated is the U.S.?

Democratic and Republican voters are now more geographically clustered within states than at any point since the Civil War, according to a recent study by economists at the University of Maryland and Northwestern University. Nearly 80% of Americans today live in a state where a single party controls both the governorship and the legislature. And there are also sharp partisan divides within states. The Cook Political Report rates about 81% of the country’s 435 congressional

districts as noncompetitive for 2024, up from 58% in 1999. That’s in part

because of gerrymandering, explains analyst Dave Wasserman, but mostly because "the electorate has simply become much more homogeneous" in many districts. A 2021 Harvard study found at least 98% of Americans live in census tracts with some level of partisan segregation. For about 25 million voters, segregation is so extreme that only 1 in 10 neighborhood encounters is likely to be with a supporter of the opposite party. "Even within a neighborhood, Democrats and Republicans are separating from each other a little bit," said study co-author Ryan D. Enos. "There’s something pretty fundamental going on here."

What’s driving geographic polarization?

Some Americans deliberately move for political reasons, such as objections to new state laws on abortion, firearms, or LGBTQ rights — and, in recent years, Covid restrictions. Lynn Seeden, a 59-year-old portrait photographer from Orange County, California, relocated to the Dallas–Fort Worth area in 2021. At her first stop for gas in Texas, "people weren’t wearing masks, nobody cared," she told NPR. "It’s kind of like heaven on earth." In one March poll, 40% of Americans said they were somewhat or very likely to relocate to a state that better fit their political beliefs. But research suggests few move solely for political reasons. A Census survey found 84% of Americans who moved in 2022 did so for jobs, housing, or family. Still, partisan sorting happens anyway because many pocketbook concerns overlap with political ones. In 2022, 817,669 people left California, 545,598 left New York and 344,027 left Illinois — mostly to low-tax, lower-cost red states such as Florida and Texas, which gained 738,969 and 668,338 new residents respectively. And geographical polarization is not simply a result of people moving, but also of long-term changes within the two parties and their constituencies.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What kind of changes?

Before the 1970s, the major parties were far less ideologically uniform. The Northeast had plenty of socially liberal “Rockefeller Republicans,” while the South had many socially conservative Democrats. But Democratic involvement in civil rights legislation led some white Southerners to switch parties, and the culture wars of the 1970s and ’80s sorted liberals into the Democratic Party and conservatives into the GOP. Over recent decades, the urban/rural divide between the parties has also expanded into a chasm. In the 2020 presidential election, Joe Biden won 91% of the country’s most populous counties, while Donald Trump took more than 2,500 of the remaining 3,000 counties. Increasingly, Democrats are higher-educated city dwellers who work in white-collar jobs, while more of the rural white working class has trended Republican.

Is partisan sorting a problem?

For individuals, it can feel comforting to live among people with similar beliefs and backgrounds, and under a state government that enacts policies they support. But such segregation could be bad for the nation’s political health. "Groups of like-minded people tend to become more extreme over time in the way that they’re like-minded," said Bill Bishop, author of The Big Sort. Such clustering can reinforce the sense that people outside the bubble are the enemy: In a 2022 Pew survey, majorities of Democrats and Republicans said they viewed members of the other party as more "immoral" and "dishonest." Under half in each party said the same in 2016. With fewer voters in the middle, lawmakers have less incentive to reach across the aisle and compromise. And with less compromise and experimentation needed, states increasingly emulate policies enacted by other states controlled by the same party — or follow the agenda of partisan interest groups such as the National Rifle Association. "The old phrase 'all politics is local' no longer applies to the political parties," said political scientist Jacob Grumbach, "but it does apply to American political institutions."

Can this polarization be reduced?

Not easily. Party affiliation has become as much a cultural identity, with its own set of lifestyle preferences, as it is a set of political beliefs. Biden, for example, won 85% of U.S. counties with at least one Whole Foods in 2020, but only 32% of those with a Cracker Barrel. Political scientist Lee Drutman argues that a radical election rethink is needed to "cool the heated polarization that is currently breaking our democracy." He’s in favor of scrapping single-member House districts and replacing them with larger multimember districts, with seats parceled out according to the percentage of the vote that each party receives. That system, known as proportional representation, would increase the number of competitive seats and force candidates to reach beyond their party’s base. Such reforms are a long shot, Drutman admits. But the U.S. is "in uncharted territory," he notes. "It’s time to take alternatives seriously while we still have time to consider them."

Transgender exiles in America

For many transgender people, the question of whether to move to another state has taken on newfound urgency. Laws banning hormone treatments and surgeries for trans-identifying minors have been enacted in at least 20 states in recent years; seven restrict Medicaid coverage of such treatments for adults. At least 10 have adopted laws barring people from bathrooms that don’t correspond to their birth-assigned sex. It isn’t yet clear whether such laws have sparked a wave of relocations. But in a March Washington Post/KFF survey of transgender Americans, 27% said they had moved to a new neighborhood, city, or state in search of a more accepting place to live. Some families of trans-identifying children have felt compelled to relocate. Earlier this year, the Noble family — whose 16-year-old son Julien is trans — moved from red Iowa to blue Minnesota. "We’ve been [in Iowa] our whole lives," said mom Jennie Noble. "But when it came down to it, we have to support our son. We have to keep him safe."

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.

Continue reading for free

We hope you're enjoying The Week's refreshingly open-minded journalism.

Subscribed to The Week? Register your account with the same email as your subscription.

Sign up to our 10 Things You Need to Know Today newsletter

A free daily digest of the biggest news stories of the day - and the best features from our website

-

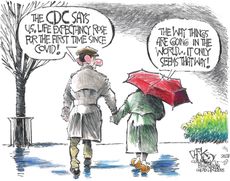

Today's political cartoons - December 3, 2023

Today's political cartoons - December 3, 2023Cartoons Sunday's cartoons - life expectancy goes up, Kissinger goes down, and more

By The Week US Published

-

10 things you need to know today: December 3, 2023

10 things you need to know today: December 3, 2023Daily Briefing Gaza residents flee as Israel continues bombardment, Trump tells supporters to 'guard the vote' in Democratic cities, and more

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

5 X-plosive cartoons about Elon Musk

5 X-plosive cartoons about Elon MuskCartoons Artists take on his proposed clean-up of X, his views on advertisers, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Should the US put conditions on Israel aid?

Should the US put conditions on Israel aid?Today's Big Question Democrats are divided on the issue

By Joel Mathis, The Week US Published

-

Why Hunter Biden offered to testify in House probe, and why Republicans said no

Why Hunter Biden offered to testify in House probe, and why Republicans said noSpeed Read Biden said he would testify in the House GOP's impeachment inquiry, but not behind closed doors

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

Could newly released Jan. 6 footage backfire for Mike Johnson and the GOP?

Could newly released Jan. 6 footage backfire for Mike Johnson and the GOP?Today's big question By appeasing his conservative base, the Republican speaker of the House may have given his party another election-year headache.

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

'The world cannot stand by to witness more slaughter of civilians'

'The world cannot stand by to witness more slaughter of civilians'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

'Drowning in plastic trash'

'Drowning in plastic trash'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

Will Rep. George Santos be fired before he can retire, after damning ethics report?

Will Rep. George Santos be fired before he can retire, after damning ethics report?Speed Read The truth-challenged New York Republican is on thin ice after a House Ethics Committee report found 'substantial evidence' he violated ethics rules and criminal laws

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

How long can the US avoid a government shutdown?

How long can the US avoid a government shutdown?Talking Point The latest deal moves the fight to January

By Joel Mathis, The Week US Published

-

'Life in 2023 means being in a constant state of sticker shock'

'Life in 2023 means being in a constant state of sticker shock'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published